I've continued watching the unfolding of the Syrian refugee crisis from out here in Canada, and was particularly interested when the professor in my "Global Warming" course suggested that the refugee crisis could be the first large-scale movement of "climate refugees". Although we only briefly touched on this suggestion in the course, I decided to extend this idea into more research for a blog post.

Firstly a climate refuge is

somebody who must leave their home because of the effects of climate change and global warming. The Syrian refugee crisis can be traced back to severe droughts between 2007-2010 when widespread crop failure, death of livestock, and rising food prices forced mass migration of farming families to urban centres (

Kelley et al. 2015). Severe 3- year droughts like the 2007-2010 drought are estimated by various climate models to have become 3 times more likely since the start of anthropogenic forcing than by natural variability alone (Kelley et al. 2015). While there were undoubtedly many other factors that led to the start of the Syrian civil war and subsequent refugee crisis (such as corrupt leadership and inequality), climate change can be seen as the triggering factor since the 2007-2010 drought forced huge numbers of vulnerable people into already tense and overpopulated cities (

Welch, 2015). Tensions erupted, civil war broke out and millions fled.

So if climate change did trigger the Syrian civil war and the resulting exodus of Syrian refugees, it is important to look at what climate models predict for the Middle East in the future. Four important factors include:

1) Temperature

As shown in Figure 1 below, although the Arctic is expected to warm the fastest, the Middle East has one of the highest temperature increases for a populated region. Temperature increases here are expected to increase by 2-3.5°C by a relatively soon 2046-2065.

2) Precipitation

Warmer temperatures intensify the global hydrological cycle, thus increasing the globally averaged precipitation, evaporation and runoff (

Wang, 2005). However, the amount of precipitation does not increase everywhere and in the Middle East, precipitation is likely to decrease (Wang, 2005). This is bad for agriculture as decreases in precipitation and general changes within precipitation patterns in the region will affect existing agricultural routines of planting and harvest, thus impacting food security.

3) Soil Moisture

Warmer temperatures will alter precipitation patterns and increase the atmosphere's evaporative demand in the Middle East, which will in general reduce soil moisture levels (Wang, 2005). Reduced soil moisture will reflect changes in agricultural water availability, thus impacting crop productivity and food security (Wang, 2005).

4) Wetbulb Temperature

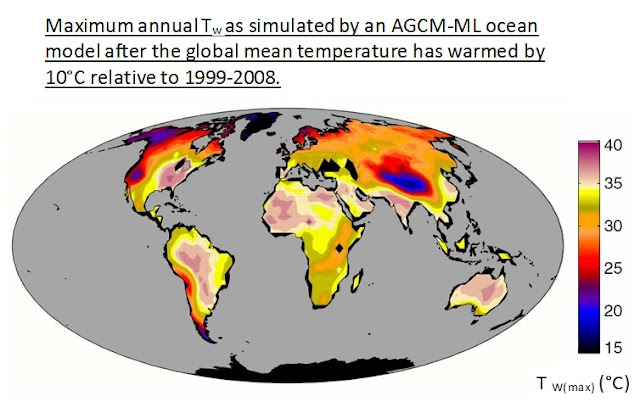

The wetbulb temperature (T

W) is the lowest temperature of the skin that can be achieved through evaporation. Since the normal core body temperature in humans is 37°C and the skin temperature is 35°C, if the air temperature is greater than 35°C, the skin temperature can be kept at 35°C or cooler through perspiration. If the wetbulb temperature becomes too high however (because the air temperature is too high, the air is very humid, or a combination of both factors), it can be difficult for the human body to lose sweat through evaporation to cool itself. During this past decade, no where on Earth has experienced a wetbulb temperature of more than 30°C (which is acceptable considering 32-33°C is realistically the highest wetbulb temperature the human body can survive), but with the planet warming, higher wetbulb temperature maximums may become frequent, endangering the lives of many, particularly the elderly and the sick. Figure 2 below shows a worst case scenario where the climate sensitivity is high and minimum steps have been taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a 10°C warming and wetbulb temperatures exceeding 32-33°C in many places around the globe, including the Middle East.

So according to climate models, the Middle East will get higher temperatures, altered precipitation patterns (generally leaning towards less precipitation), lower soil moisture and increasing wetbulb temperatures, all of which will decrease water security, food security, ability of the human body to survive and increase tensions over scarcer resources. If the current Syrian refugee crisis is indeed because of drought, we may see more climate refugees as water stress and food insecurity increase further, along with heat stress.

A note about the 2015 Paris Agreement

The 2015 Paris Agreement has been hailed by the many as a significant step forward against global warming and I've seen many of my own peers praising the agreement's decision that the global warming target should be a limit of 1.5°C rather than 2°C. But the reality is that even with the lowest, most optimistic greenhouse gas emission scenarios for the future, we're still looking to have greenhouse gases peak at the equivalent of a CO

2 doubling. The climate sensitivity (the eventual global average warming for a fixed doubling in the concentration of CO

2) is estimated with 90% confidence to fall between 1.5-4.5°C, so considering greenhouse gas concentration increases that have occurred so far are equivalent to a 75-100% increase in the atmospheric CO

2 concentrations,

we are already committed to a 1.5-4.5°C warming. Even if the climate sensitivity turns out to be low, a 1.0-1.5°C warming is far from safe, with eventual consequences including several meters sea level rise, widespread ecosystem damage and increasing drought and water stress (which we're already seeing with our current 0.8°C observed warming, as evidenced by the Syrian crisis above).

Thus the Paris Agreement's decision to limit warming to 1.5°C is not helpful to global warming efforts. We cannot just pick a number and say warming will stop at that number; it is nature and the climate sensitivity that will determine just how dramatic warming will be for a doubling in CO

2 (or its heat trapping equivalent of greenhouse gases). The Paris Agreement would have done better to focus on encouraging all countries to reduce their anthropogenic CO

2 or all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by for say, 2060-2080. Indeed, the original draft text for the Paris Agreement planned to discuss reducing emissions to 0, but its removal shows obvious avoidance of disrupting current models of unlimited economic growth that use fossil fuels, while focusing on catchy numbers (1.5°C) to reassure the general public that the governments are supposedly doing the best they can.

Realistically, if we want to minimise the possibility of future large scale climate refugee migrations, we need to reduce emissions to net zero as soon as possible.